Isabel Moreira discusses her new study of Balthild, Queen of France

Robert Carson, Associate Director, Tanner Humanities Center

February 24, 2025

In the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris stand twenty white marble statues of queens and

illustrious women in French history, a series commissioned during the 19th-century

reign of King Louis-Philippe as part of a larger beautification program. However,

when sculptor Victor Thérasse presented his statue of Queen Balthild in 1848, both

the statue itself and the figure it represented had unique significance. Thérasse

has Balthild holding an open book to her shoulder. On its revealed page, facing outwards

and not easily legible to visitors, is inscribed Abolitio servitutis—abolition of slavery.

In the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris stand twenty white marble statues of queens and

illustrious women in French history, a series commissioned during the 19th-century

reign of King Louis-Philippe as part of a larger beautification program. However,

when sculptor Victor Thérasse presented his statue of Queen Balthild in 1848, both

the statue itself and the figure it represented had unique significance. Thérasse

has Balthild holding an open book to her shoulder. On its revealed page, facing outwards

and not easily legible to visitors, is inscribed Abolitio servitutis—abolition of slavery.

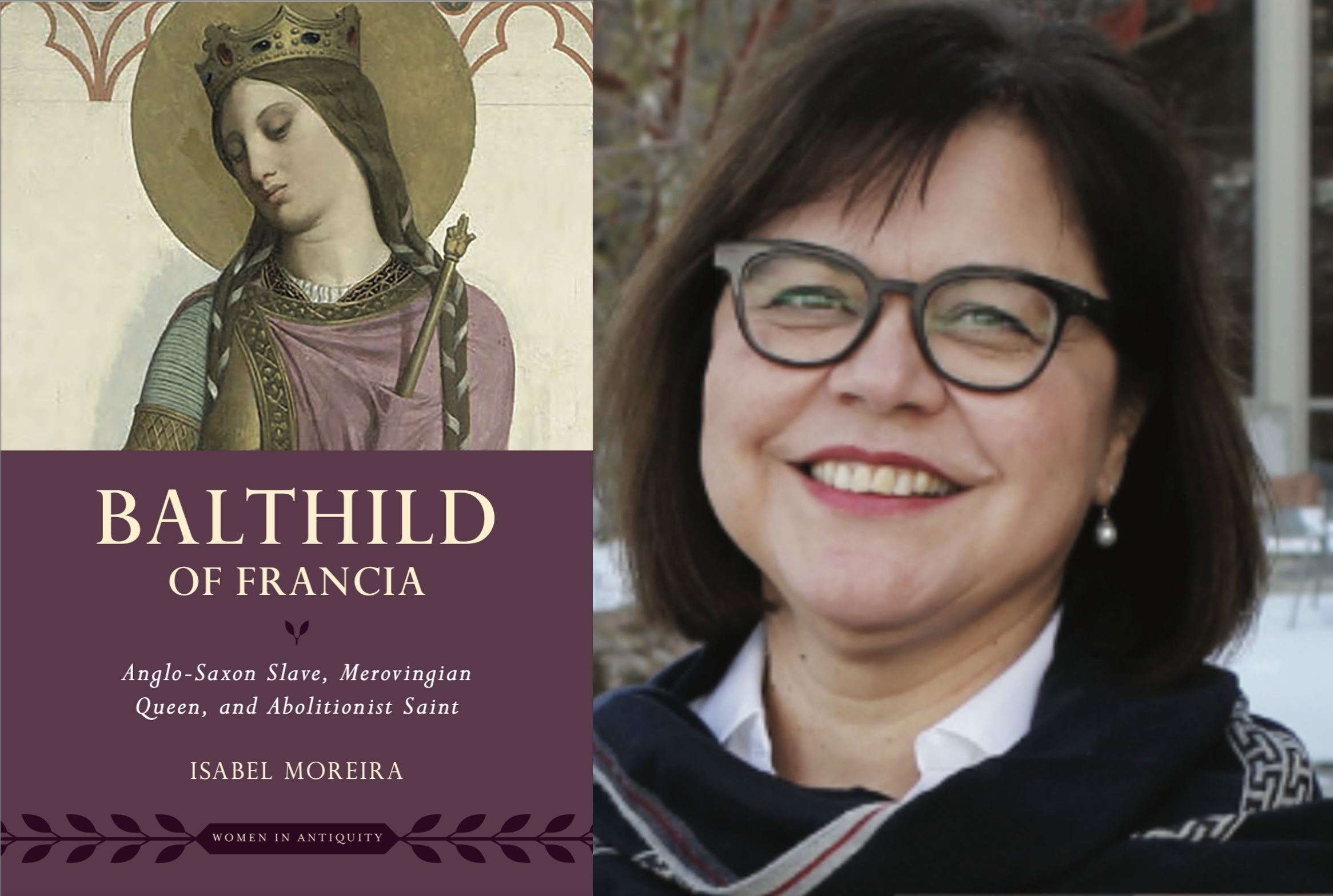

Who was Balthild, and what does it mean to identify her with the abolition of slavery? This is the central question of Isabel Moreira’s book, Balthild of Francia: Anglo-Saxon Slave, Merovingian Queen, and Abolitionist Saint, published by Oxford University Press. At a Tanner Conversation on Thursday, February 13, Moreira (Distinguished Professor of History and Associate Dean of Research in the College of Humanities) discussed her book with Chris Jones (ESRR Professor of English).

As Moreira’s subtitle suggests, the course of Balthild's life (ca. 633–680) was dramatic, as was her afterlife. Known variously as Balthild of Chelle, Balthilda, or Saint Bathild, she was born in Anglo-Saxon England, though the exact region remains uncertain. During her adolescence, she was trafficked across the Channel to Francia during a period of significant slave trading between Britain and the continent. She was purchased “for a low price” by Erchinoald, the kingdom’s chief administrator. In an extraordinary turn of events, she later married King Clovis II and bore three sons, each of whom would eventually become king, as part of the Merovingian dynasty of Frankish rulers.

As Queen consort and regent, Balthild reigned over the same enslavement practices into which she was sold as a young girl. Slavery in Merovingian society dated back to Roman times and relied on a steady influx of trafficked people, particularly Saxons during periods of political upheaval in England. While Balthild did not challenge the fundamental institution of slavery, she implemented significant reforms, particularly prohibiting the trade in Christian slaves within her kingdom. In many ways, Balthild’s rule demonstrates the transitioning of social institutions from imperial Roman norms to those of medieval Christianity. Balthild also established programs to rescue trafficked girls and women, often housing them in convents she founded—though Moreira suggests these women may have served as domestic workers rather than becoming nuns themselves. This targeted focus on the slave trade, rather than slavery itself, parallels the strategy of later abolition movements: nineteenth-century French abolitionists found in Balthild a compelling national predecessor.

As Moreira demonstrates in her book and discussion, the canonization of medieval figures can make the task of reconstructing their lives challenging in unexpected ways. The primary source for Balthild’s life is a hagiography written within a decade of her death. While it follows the conventions of saints’ lives, it provides notably detailed information about her rule. However, the text also includes curious episodes seemingly designed to establish her virtue, such as a story about her hiding in a pile of rags to avoid a man’s advances—a detail that reveals more about the period’s anxieties regarding enslaved women’s vulnerability than about Balthild herself. Furthermore, archeological evidence can complicate the written record: the discovery of hair dye in her preserved locks suggests that she maintained her appearance even in the convent, contrary to hagiographical claims of strict religious austerity.

Moreira’s book not only presents an account of its subject, but also reveals the research methods used to establish that account, including where the historical record requires our rigorous skepticism or speculation. Balthild of Francia: Anglo-Saxon Slave, Merovingian Queen, and Abolitionist Saint is part of the Women in Antiquity series of Oxford University Press, which features compact and accessible introductions to figures like Balthild.