On Death and Memory: Alice Dailey, author of Mother of Stories

with Lindsey DragerAlice Dailey recounts the life and death of her mother, who was “a gifted teacher, a passionate reader, and a pathological liar.”

Dailey is Professor of English and Director of Faculty Affairs at Villanova University. She discusses her scholarly memoir, Mother of Stories: An Elegy, with Lindsey Drager (Assistant Professor of English, University of Utah).

Episode edited by Matty Glasgow and Ethan Rauschkolb. Named after our seminar room, The Virtual Jewel Box hosts conversations at the Obert C. and Grace A. Tanner Humanities Center at the University of Utah. Views expressed on The Virtual Jewel Box do not represent the official views of the Center or University.

-

[This transcript is automatically generated and may contain errors.]

Scott Black: Welcome to the Virtual Jewelbox Podcast of the Tanner Humanities Center. I'm Scott Black, director of the Tanner Humanities Center. Our first episode is a selection from a Tanner conversation about Alice Dailey's, memoir of her mother's death, mother of Stories, an Elegy, published by Fordham University Press in 2024.

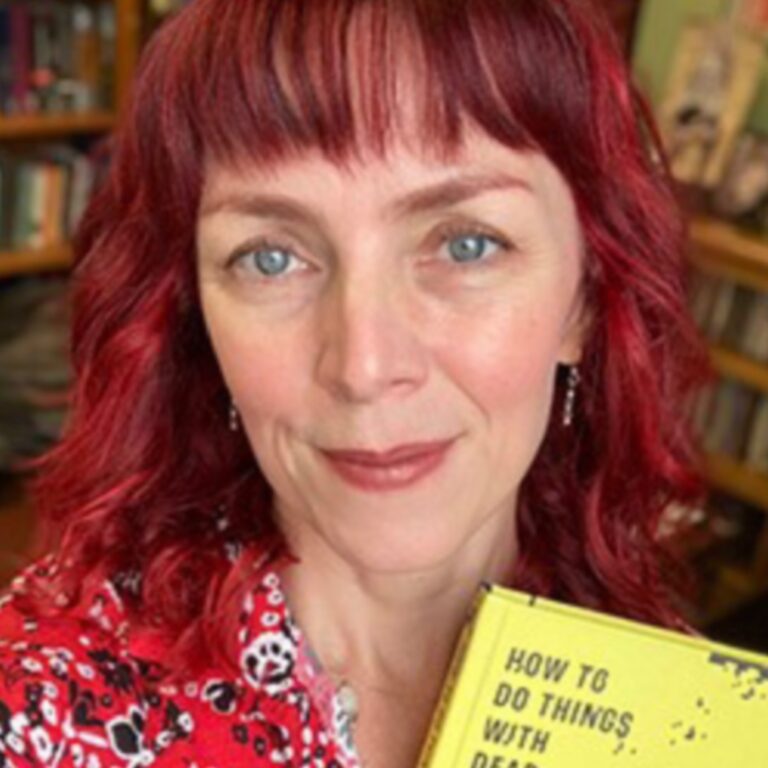

Alice Dailey is Professor of English and Director of Faculty Affairs at Villanova University. She's the author of two scholarly studies of early modern British Literature. The English Martyr from Reformation to Revolution. I. How to do things with dead people. History, technology, and temporality. From Shakespeare to Warhol, Alice's academic work focuses on the way death has been understood and represented martyrology and technologies of memory and memorial.

Her memoir is her first work for a more general audience and offers a stunning meditation on the processes of grieving from the perspective of a daughter, mother, and scholar, providing fascinating insight into the ways our personal and professional lives intersect at pivotal moments for her Tanner conversation.

Alice was joined by Lindsay Drager, assistant professor of English and Creative writing at the University of Utah. Lindsay is the author of four novels, including The Lost Daughter Collective, and the Avian Hourglass, which has just been published by Zinc. Her work has been recognized with a wide range of awards, including an NE, A fellowship, and the prestigious barred fiction prize.

Lindsay is also a wonderful teacher and was awarded this year's Ramona Cannon Award for Excellence in Teaching in the Humanities. Welcome Lindsay.

Lindsey Drager: Thank you so much for that introduction on the, and thanks for the opportunity to talk a little bit about, uh, my conversation with Alice. So my first question for Alice was about the relationship between her scholarly work and her more personal creative work.

This is her first memoir. She is, she has published extensively academic on academic presses, and I was curious about the relationship between the personal and the scholarly in this book in particular.

Alice Dailey: In terms of the question about the relationship between the scholarly and the creative self those identities for me have become a little more coherent with one another.

Through the course of writing this book, which as you mentioned, reflects in a number of ways on the how my scholarly work, is a space in which some of the deeper questions that come out of my background, my family are being worked out through, um, a, a disciplinary apparatus. That is something I learned through the course of my graduate education.

Right. And through the course of being a junior faculty member and scholar. So lots of the questions that I'm working with as a scholar of martyr literature come from. My family come from Catholicism, um, which is part of my background. And so those identities have always been related to one another. But what I learned in graduate school, um, and talk about some in the book was that the scholarly space was not one in which the personal parts of that could surface.

I had to find ways to address the questions that canum around that through an apparatus A that was fundamentally professional, right? Scholarly. In this book, those things collapse into one another

Lindsey Drager: frequently,

Alice Dailey: and I go back into my scholarly work and cut. And rearrange and cover up in order to disclose the, the, the other story that has always been under there, which is the story of, of my personal life.

Something else was happening simultaneously in reverse, which is that I was writing the how to Do Things with Dead People book while I was working on this. And as my mother was dying, I began to develop in the Dead People book a Wish to include a Coda that was autobiographical. And so that book is highly theoretical.

It is a, you know, about literary history and also a range of other artifacts as Scott mentioned. Um, but it ends. A piece about my son who had been through the course load by writing that book, dressing Up for Halloween as characters in the book as Andy Warhol, as Shakespeare, as Bowie. And so I, I allowed myself in part because I had done this book to.

Let those two parts of my brain work together to bring things to conclusion. And so I, I increasingly see them as inseparable even as I'm moving into university administration. Uh. Though they're, you know, they're all sort of working together in a, in a way that I hope will create a humane scholarship and a humane form of leadership and, um, an acceptance of the messiness that is the human person.

Lindsey Drager: My next question for Alice Orbited around a particular section of the book where she talks about kind of inhabiting other identities, it was curious to me the ways in which. She embodied her mother as a character, but also her mother was a real person in the real world. So I wanted her to talk a little bit about the relationship between her mother as a lived experience and her mother as a character that she was replicating in her memoir.

Now you talk about this moment where, and I'm gonna say Alice's son, just to make a distinction between Alice, the narrator in the book and the human Alice in front of us. Where else's son is playing Ziggy Stardust and sort of dressed up as Z Stardust for Halloween. And he just, what? That David Bowie has died.

Um, and he asks, what does it mean? Does that also mean that Siggy Stardust is dead as well? And Alice, the narrator and mother responds that Siggy Stardust is a character and a character doesn't die the way a person dies. And so I'm curious if you could talk a little bit about, um, in a book about the death of your mother, you sort of turning her into a character in the book.

And this I think will come back to a razor in, in what you decided to leave out. But could you talk a little bit about just that. Process of taking this really complex woman and translating her into essentially a character in this text.

Alice Dailey: Um, some of the difficulty of doing that for me is that I, I'm don't have creative writing training.

And this is my first work of creative writing since my early twenties. So I did not, I stopped doing that. So I don't know how to write dialogue. I have no idea. And as I. Recall as I recalled conversations with her, things I wanted to, that felt central to what I was doing here. I struggle a lot with how to represent her and the tension between.

Representing her always is a figment of my memory and trying to represent her voice and it was very difficult. So there were a few key conversations that I recall as clearly as I imagined I recall them, you know, and could hear her in my mind and produce her. I. In some of the ways that us, a playwright would create dialogue, right?

Or create direct discord, um, with a character. But in many other places, I am narrating her. And I tried to be extremely conscious of that and resist the moments where it felt like it should break into dialogue. But I would've had to make the di make the dialogue up. I couldn't remember it. Um, and to not turn her.

As much as it's possible to not turn her into a fictional character. But of course even as I talked to, for example, my siblings they both recognize her in this book and recognized her as my, her right. She can't possibly be also there. So I had done something to her here. Is to take possession of her in the way a playwright takes possession of a character and then tris through that historical perin a set of things that that person probably never said.

Lindsey Drager: Yeah. And then even, even your retrospective reconstruction is a different Alice than the Alice you represent in the book, who's dealing with and coping with his like extraordinary loss, but also the complex kind of. Rhetoric around that lost. She still needs to be a professor. She still needs to be presenting on death in order in her scholarship, as well as dealing with it in the career personal way.

So it's really interesting to think about not just that split between the real and the construction or the artificial in terms of the mother character, but also the Alice's character. I was fascinated by the replication of dreams and coincidences across the memoir. There are many places where. Her experience as a professor and her experience on the page in her work were, were replicating or echoing each other.

I was curious if she could talk a little bit about recurring dreams and also coincidences.

Alice Dailey: I had a recurring dream from many years as it began after my grandma LA's death. She died of lung cancer when I was seven, and I was given her bedroom furniture, the queen sized bed with sliding panel storage covers built into the headboard. Felt luxuriously. Huge for a child my size. But it smelled like my grandmother's house on Yarmouth Avenue, like schnauzers and cigarettes.

Overlaid with Ri, the furniture arrived empty, but for the dresser's scented drawer paper and a few stray perfume soaps who smelled thickened into a spectral atmosphere that clumped my room. Room. My sisters and I eventually threw out the paper in soaps, but the smell never went away. I would dream that I was floating above this bed almost attached to the ceiling.

In one corner of the room, looking down at myself, sleeping across two of the other corners, spanning the room Diagonally was suspended, some kind of tendon or muscle, a cord of tissue that slowly rhythmically contracted and released over the sleeping girl. She did not feel its contractions. It was I who felt them that I could do nothing but hold my dread in silence and wait for them to subside.

Just yesterday, I experienced a brief waking deja vu of this dream, A dream I continued to have even after we moved to the Philippines and left my grandmother's furniture in storage on the other side of the world. Although I still recognize the dream, the instant its feeling comes over me, I cannot conjure up its effects at will, even if I can picture the suspended muscle.

The dream is not an image. It is a tension, a tinny nerve, taut and plucked at the heart of me close to the bone. It's a rhythm of terror that ease in my jaw.

Lindsey Drager: Ah, love that. I think it's such a perfect sort of, um, it provides a kind of Petri dish for the larger concerns of the book, right? There's this doubling of the Alice who's looking down at the Alice in the bed.

There's a tendon, which you also describe as a tension. So there's like this really interesting kind of language play happening there. And then there's the waking deja vu of imagining one has lived this, but of course it was a dream. So where does the dream world and, and the sleep world. And I just found that so, so moving and I, it makes me think this tendon, this tension makes me think a lot of legacy.

Alice Dailey: Hmm.

Lindsey Drager: Um, and family history and reconstructing family history is fundamental to the, to, to the book as well. But another way of thinking about legacy is citation. You, which you talk about quite extensively. And so I'm thinking, you know about, um, the parts of the book that talk about like you kind of inheriting or Shakespeare inheriting history to make the history plays, right?

And then you inheriting. The, the legacy and those who have come before you, kind of Burke and Parler style, you're entering the conversation. So you have this conversation that's already existed before you, you were born. And I'm thinking about that, that image of the, the tether, the tension in this muscle.

And I'm wondering if you could talk a little bit about, um, how you teach the history plays that tension or tendon between. Artifice on the stage and reality. Um, and, and also maybe just talk a little bit about like, legacy for you, the scholars that have been important to you or how your relationship to the scholars who have come before you in that kind of tending tension.

Alice Dailey: Yeah. There was an interesting moment where when I was writing about writing about the history plays and trying to think about whether. The inheritance that I had received was fundamentally a patriarchal one or a matriarchal one, and it's both, but it is. Predominantly matriarchal. There has been a, the history plays oddly have been dominated by female scholar and suspicion for the last three years or so.

So there the, it was a kind of strange moment of why am I even trying to decide whether this comes from men or comes from women. But it had something to do with sorting out my place in that. And whether, I am. I am doing something as a woman or doing something as you know, a person who can't help inherit what men have done.

Um, so I, I have been sort of conscious of intervening and, and participating in various kinds of critical traditions and also trying to reinvent them. And so I taught some in the beginning of the history plays book about, seeing my rather bizarre, admittedly, like I describe it as strange intervention in the history plays as one that's informed fundamentally by a feminist politics of of difference.

So when I teach them, I, I try to teach mainly what Shakespeare is doing as a dramatist. We taught some about actual history. You have to give them, you know, the quick and dirty version of the war. And how we get from point A to point Z, but a lot of what I do is to think about vent causing the dead.

And what, what purpose does the dead serve? How we can do things with them and through them, how we use them to look at ourselves, to think about ourselves, to imagine the future and what the politics and ethics of that imagining are. Whether, you know, there's something wrong. With repurposing dead people, um, in order to tell stories that we wanna tell whether there's something either good or bad about staging a history play that translates, its, its entirely out of its original context and into our own.

Are we then, um, colonizing the past in ways that are for our own. Purposes and benefits. I think the answer is yes, and also that's what we're always doing.

Lindsey Drager: Yeah.

Alice Dailey: With the debt and it's to me. This is one of the places I come to in the memoir. Fundamentally, the difference between the dead and the living that the dead don't have agency and the living do, and that accepting and embracing the agency or the living is what it means to be alive.

And it's a thing that my mother did.

That she was attached to the dead and re recirculating the dead. That gave her no way out, you know, and so, the history plays are both a scripting of the past and a scripting of our relationship to it, but also an opportunity to re-inhabit and remake all the time what has come before us.

Lindsey Drager: My final question for Alice had to do with what she left out of the text or what she ultimately erased from her memoir. As we know, memoir is a condensation or a distillation of real life, and I wondered what didn't make it in the memoir that she might have wanted to in an earlier draft. There, there are images of kind of family photographs where.

The mother has been sort of erased and, and there's all kinds of erasure happening, like the, the literary art of erasure happening throughout the book as well. Um, and so this is a little bit of a, not as a, not as critical of a question, but I'm just curious. Any, like, we're talking about any historical figure is a reconstruction.

What did you leave out? What did you choose? Not, I mean, I'm fascinated by this research of the Folger that didn't make it in any other, anything else that felt, either you felt like you had a self-censor or you felt like you did not want to put on a page for either personal reasons or because the construction would've marked away from what you wanted.

Alice Dailey: It's mostly the last bit that you know, for better or worse, these kinds of things end up with a shape and then, um, material that seems related or connected. Doesn't necessarily fit into that shape. And so it gets left out. Um, Scott and I were talking this morning about a sort of sidebar story that I would've loved to include and couldn't find a place for.

That has to do with the guy I had the car accident with. I had this car accident after my mother died with a person who claimed. To have lost his father in the same month that my mother died. I think that was probably a lie. I think he made that up because in the conversations that we had we had a, a sort of brief friendship.

He told me several other things about his father that we utterly incoherent with what he had initially told me. So I'm pretty sure his father did not die at that time in the way that he said. But also of, he introduced me to Murakami. He gave me Kafka on the shore, and I then started reading Murakami and he had told me a number of stories about his life.

I then discovered he would saying, founded by, and there, so there was this weird, speaking of repetition, there was this weird way that he would, I had had a literal collision with a pathological liar. In the course of writing a book about my mother. Who was a pathological compulsive liar. And he was also in this, in this way, that the book is very interested in living out or at least narrating a version of self that was a hybrid of autobiography and fiction.

And so it was just a crazy, you know. Confluence of all the things that I was working on. In this person. But it didn't make it in because it was such a, it's kind of a whole thing, right? That, that I didn't have the space for. Another thing I struggled with, um, wasn't an episode that happened in the hospital.

During the period it was my mother was hospitalized. It seemed like she was gonna die. So it was for me at the time, a deathbed experience. You know, her, on her deathbed. She didn't die then she died a couple weeks later. Um. She was asleep and dreaming and sat up in bed and started to talk as though she were in a play and she said, I can't go on.

She's, and I thought at first she was talking about, you know, her life and dying. And then, you know, she repeated several times. I can't go on, I can't go on. And then said my costume isn't ready. And I let this unfold briefly and then started to, 'cause she was getting distressed to reassure her that she was not, there was nothing happening.

She was fine. She was okay. She's in a hospital, there's no play. And then she quickly gained some kind of consciousness and was embarrassed and said in this kind of nasty voice, I know that. And laid back down and then was out, like out again. And so in the book, I talk about the way she asked me at one point in those couple of days to read er, not to pee to her.

So there were these strange kind of, the theater is becoming a bed, the bed is becoming a theater. I don't know if I'm who I am here. Am I Hamlet? Am I the stage manager? It was this, it was a really odd con again, sort of confluence of events that circled around my own intellectual interests and these, the thematics of repetition and recreation that are so central to all of Redler.

Yeah. And

Lindsey Drager: coincidence, parallel. And I, I'm thinking too, just the ways in which the two anecdotes you just offered so perfectly crystallized, the fictional versus fictitious. I was getting at, at the beginning of kind and trying to introduce this book where the fictional, and I'm not, this is not my thought.

I'm scaling this from Doric Cone who wrote the distinction of fiction. Okay. I need to slight myself, but she sort of talks about like the fictional is something we move toward because it reveals some kind of truth, whereas the fictitious is something we like. Dispel because it feels like it's, a trick to us.

Yeah. And that I like that kind of oscillation or oscillation between those two spaces is just pervasive. Yes. So interesting.

Alice Dailey: Yeah, and I think, you know, there it is part of the sort of peacemaking that this project was for me. That I was so adamant in my own psyche all the time in relation to her about what was true and what was false, because she just was a comp.

She lied all the time about anything and everything, and so the experience of being her daughter was one of. Saying nothing and also reserving in this way. That reminds me of Jesuitical provocation, which is a research area of mine too. Reserving in my head. The real thing, uh, which was that is complete bullshit and I know that, and you know that, but we're not saying that.

But part of what writing these stories down and realizing that I could never write them accurately, there's no such thing was a, a humbling encounter with a. The impossibility of telling the truth or of discerning what it even is. And the multiplicity of truths that coexist in any relationship.

Psyche, right? Experience, piece of literature. There is a way that the book seeks, I think ultimately to undo its own truth claims, um, as a project. And the purpose of that is to honor for me what is the lived experience, which is, is messy, but also to sort of be a better daughter and accept that, the hardness with which I held that distinction is not what I can continue to hold in the face of my own storytelling actions.

Lindsey Drager: It seems significant that the very end of the book is Alice Reading or Is Alice sort of thinking about her mother? And then I asked her at the very, very conclusion to talk a little bit about the ending, which seems significant given the title of the book, the Mother of Stories.

Alice Dailey: So this is hard for me to read, so if I do so robotically, it's because that's how I'm getting through it. Uh, but I do love it. So thanks for by me. In the midst of ancient Greece, the shades of the dead had to drink from the river leafy before crossing into the underworld. The waters of lety induced amnesia, allowing the dead to enter the afterlife free of the memory of life on earth.

I imagine my mother at the edge of this river, she knows what she's supposed to do. She has read all the books, but she does not take a drink as the other shades do. Instead, she dips in a toe and then a foot a. Then she wades into the current and begins to cross her feet and legs. Her torso and hands, and arms and shoulders.

Her beautiful face. The face of my mother vanishing forever. In the swirling water on the far bank, something emerges that no human word can name. It is brilliant and fantastical. A form or perhaps a formlessness, too abstract, too otherworldly for our minds of clay to imagine it rises from the water.

Disappears into the future.

Scott Black: That was Alice Dailey reading from her memoir, mother of Stories, an Elegy, and answering questions from Lindsey d Drager, professor creative Writing here at the University of Utah. Thank you for joining us and for your attention. Here's some more of Jelly Roll Morton's Perfect rag.

Alice Dailey